Clément Serneels

(1912 – Brussels - 1991)

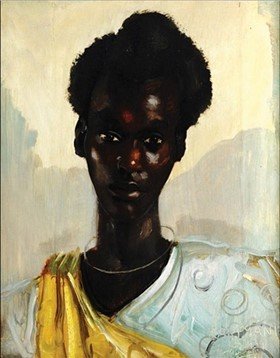

Portrait of Tutsi regional chief Ntwarabakiga

signed and dated 'Clement Serneels/1939' (lower left) and inscribed 'NTWARABAKIGA/NIANZA'

oil on board

19 x 15 in.

Provenance

Private collection, United Kingdom, acquired in 1941, and by descent

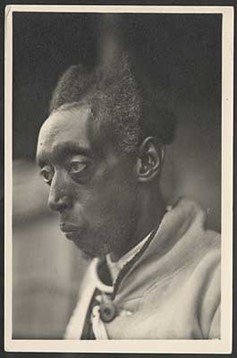

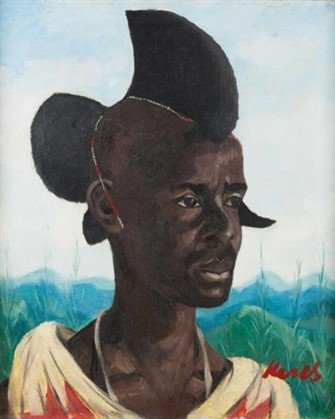

This captivating portrait of a man, painted with rich, virtuoso brushstrokes, is signed by Belgian artist Clément Serneels and dated 1939, when he is recorded travelling across Central Africa. The first clue as to where the canvas was painted and as to the identity of the sitter, which is discussed below in detail, is his hairstyle: Amasunzu. A Rwandan tradition reserved to men and unmarried women, it signals social status and attributes such as strength or, in the case of women, virginity. The hair is parted into crests, often crescent shaped, which curve across the head of the wearer and endow him or her with a strikingly distinctive appearance. The sight of Amasunzu no doubt impressed foreigners visiting Rwanda after the institution of colonial rule, as the work of photographers such as Casimir Zagourski (fig. 1) and painters such as Henri Kerels (fig. 2) testify. This fascination arguably stemmed not only from an aesthetic interest, but from an approach to Africa deeply rooted in colonialism, where recording the difference, the “exoticism”, of the local population to European canons reinforced the premises of the colonialist agenda.

Before arriving in Rwanda in 1938, Serneels had already visited the Central African nation and neighbouring countries in 1936-37, thanks to a government grant secured for him by his alma mater, the Académie de Beaux-Arts de Bruxelles. Serneels exhibited the paintings from his first African trip in an exhibition that quickly sold out in Brussels, the proceeds of which allowed him to independently return to Central Africa in 1938. The artist spent the WW2 years in Costermansville (modern-day Bukava), on the south-west shores of Lake Kivu in what was then Belgian Congo, moving to South Africa in 1945, where he held a number of acclaimed exhibitions. His works continued to enjoy solo shows in his native Belgium, and in the United States and Mexico. Serneels returned to live on Lake Kivu from 1953 until about 1960, when the end of colonial rule saw him move back to Belgium.

Serneels’ oeuvre, comprised chiefly of portraits and landscapes, is stylistically anchored in post-impressionism. As in the present case, his sitters are often depicted against an unadorned cream or ochre background that echoes the paintings of Édouard Manet, albeit suffused with the brightness of the African subcontinent’s light. Similarly, Serneels’ brushstrokes show a fluidity and immediacy that also recall the work of the French master, alongside that of others such Paul Cézanne, whose baskets of fruit appear to be the predecessors to the terracotta vessels and fruits featured in Serneels’ portraits from Central Africa (figs. 3-4).

At the time of Serneels’ first visit, Rwanda had been a Belgian colony, alongside neighbouring Burundi, since 1916. Yet the history of colonial rule in the area had begun earlier, in 1885, when the Berlin Conference had drawn the boundaries of German East Africa, which included present-day Burundi, Rwanda, the Tanzania mainland, and a small region of Mozambique. Under colonial rule, Rwanda continued to be a monarchy, albeit its king (the Mwami) was relegated to a figurehead role. As scholars have observed, nineteenth-century European theories on race heavily influenced the colonizers’ approach to the complex social fabric of the occupied territories and, in Rwanda, successive colonial governments favoured the population of Tutsi ethnicity, based on the fact that Tutsi nobility had long ruled over their Hutu and Twa countrymen. This construct originated in the three ethnicities’ traditional yet porous split between nomadic pastoralists (Tutsi), sedentary farmers (Hutu) and hunters (Twa). As cattle ownership represented the primary indicator of wealth, the Tutsi held the highest positions of power, but their Court ruled over a multi-ethnic society that shared one language and the same societal and religious traditions. It is important to note that European “race science” also stressed the superiority of the Tutsi based on their physical archetype – a tall, elongated body with high foreheads and cheekbones, narrow nostrils, and long necks – which was praised in contrast to the supposed shorter and stockier appearance of the Hutu and Twa. These considerations likely informed the work of artists such as Serneels, who appears to have favoured painting Tutsi subjects while in Rwanda.

The interest of European occupiers in the Tutsi is exemplified by the book Généalogies de la noblesse (les Batutsi) du Ruanda (1950) by Belgian Catholic missionary Léon Delmas, which offers a detailed record of generations of Rwandan Tutsi chiefs and their offspring. The account, whilst not based on a scientific approach, was the result of years of activity in Rwanda and careful collection of information from local residents. Among the descendants of Yuhi IV Gahindiro, a Rwandan ruler whose reign – from 1792 to 1802 – is remembered as the most peaceful in the kingdom’s history, Père Delmas lists a former regional chief (“sous-chef”) named Ntwarabakiga, son of Cyitatire, son of Rwangeyo, son of Nyivindekwe, eldest son of Yuhi IV Gahindiro (Delmas, 1950, p. 80). The name Ntwarabakiga is inscribed on the lower left of the present canvas, accompanied by the word Nianza, an erroneous spelling of “Nyanza”, an ancient city that was declared the first permanent royal capital of Rwanda in 1899 and kept this status until the country became an independent republic in 1962.

Further testimony of Ntwarabakiga and his position within Tutsi hierarchy can be found in the account of another member of the local clergy, Abbot Alexis Kagame, who authored a treatise on the history of cattle herds attached to army groups in the kingdom of Rwanda. Ntwarabakiga, we learn, succeeded his older brother Hajabakiga as the heir to their father Cyitatire, and at the time of writing was living in Nyarubaka, in the province of Nduga (Kagame, 1961, p. 24). It is therefore likely that Serneels encountered Ntwarabakiga – for whom there is no birth date on record – in Nyanza when the Tutsi was still a young man, as the portrait suggests, whilst Delmas and Kagame knew of him many years later, after he had served as a regional chief.

Nyanza, being the kingdom’s capital, is where, as Père Delmas explains in his book, all chiefs, guardians of tradition, chroniclers, “living national archives”, poets and troubadours regularly converged. It is perhaps this rich heritage that attracted the young Serneels to the city in the first place, where he encountered Ntwarabakiga, who may at the time have been enrolled at the local school for children of Tutsi chiefs established by the Belgian authorities.