Paula Lauenstein

(1898 Dresden – Crostau 1980)

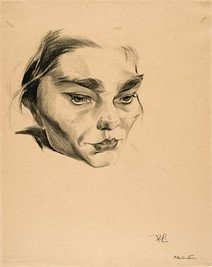

Hans Nötzel, sitting on a chair

Pencil on Simili Japan paper

Signed and dated (lower left): “11. Jan. / P.Lauenstein”

The author of this powerful pencil portrait of a seated child is the German artist Paula Lauenstein (1898-1980). Born in Dresden to Wilhelm Lauenstein, a commercial director, and his wife, a teacher, Paula was educated at the city’s Municipal School for Girls, and separately began to receive private drawing and painting lessons in 1914. Her first tutors were local artists Max Starke (1873-1944), by whom very little is recorded today, and Richard Burkhardt-Untermhaus (1883-1963), who worked chiefly as a landscape painter and draughtsman.

Lauenstein’s formal artistic education began in 1916 at the Dresden School of Applied Arts, where she was taught by painter and printmaker Max Feldbauer (1869-1948), fashion and interior designer Margarete Junge (1874-1966) and later Paul Rößler (1873-1957), a painter, restorer, and stained-glass designer. In 1920, Lauenstein was amongst the first female students admitted to the Dresden Academy of Fine Arts, the city’s most prestigious art school, where she continued to be mentored by Max Feldbauer. In 1923, her still life Opuntia (Nationalgalerie, Berlin) won the State Academy of Fine Arts’ prize, and she graduated the following year.

The present drawing, which bears the inscription “11 Jan.”, likely dates to 1924, the final year of Lauenstein’s course at the Academy of Fine Arts. The sitter’s distinctive traits correspond to those of Hans Nötzel, a child recorded to have worked as a model at the Academy, also immortalized in the drawings of Lauenstein’s fellow students Alice Sommer (1898-1982) and Gerd Böhme (1899-1978). Nötzel was the subject of a small number of works on paper by Lauenstein, two of which – dated 1924 – were published in the catalogue of the exhibition Paula Lauenstein, Elfriede Lohse-Wächtler, Alice Sommer: drei Dresdener Künstlerinnen in den zwanzigen Jahren, held at the Städtische Galerie in Albstadt (November 1996 to January 1997).

Following her graduation Lauenstein engaged with Dresden’s artistic circles, writing two articles on fellow painter Elisabeth Ahnert (née Röth) and on the graphic designer Ruth Meier. In 1928, a selection of her drawings was exhibited at the State Museum in Bautzen, a town east of Dresden, in Upper Lusatia, the region where her family owned a country residence, and that had featured in her landscapes since the days of her training at the School of Applied Arts. She further developed her interest in landscapes in 1930, thanks to a sojourn in the Allgäu, a mountainous region of Bavaria. After 1933, Lauenstein began to move more frequently, spending much of 1934 in Munich, followed by Berlin, and then Wetro, at her parents’ home in Upper Lusatia. In 1937 she was shortly in Salzburg, and the following year she set up a studio in Munich, at Rubensstraße 8, which was destroyed by bombs in 1941. She then returned to Wetro, and continued to live in Upper Lusatia until her death, in the town of Crostau, in 1980.

Lauenstein’s activity as a painter and draughtsman is concentrated between her Academy years in Dresden and the beginning of World War 2. While still a student, her style was influenced by that of her teachers, principally Feldbauer, and more broadly by French masters such as Manet, Renoir and Cézanne. Three oils on canvas she painted between 1921 and 1922, now in the Staatliche Kunstsammlungen in Dresden (figs. 1-3), perfectly illustrate this stage in her career. Paint is applied in parallel brushstrokes and with varying degrees of saturation, the effects of light are conveyed through colour, and each picture is endowed with a rhythmic sensibility – such as between the fence posts and belltower in the view of Neustadt – that testify to her compositional skill.

At the time when she executed the series of portraits of Hans Nötzel – ranging from closely observed pencil studies such as the present sheet to looser sketches – Lauenstein was finessing her technique and simultaneously exploring the expressive possibilities of her work. Here, she appears to look at Hans from a raised viewpoint, and focuses on rendering his head and torso frontally, while his legs are at a slight angle. Equal attention is paid to his large eyes and their air of seeming expectation, as they gaze silently yet intently at the viewer. This sensitive treatment of the sitter, combined with an unflinching representation of his features, is typical of Lauenstein’s 1920s production (figs. 4-6), and it explains why her works have been exhibited alongside those of masters from the German Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity), such as Otto Dix, Christian Schad and Alexander Kanoldt (Surreale Sachlichkeit. Werke der 1920er- und 1930er-Jahre aus der Nationalgalerie, Berlin, October 2016 – April 2017).