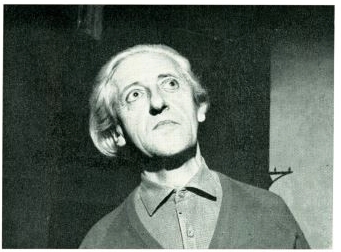

MARCEL DELMOTTE

The son of a glassblower, Marcel Delmotte (1901-1984) spent his entire career in the mining and steel manufacturing Belgian town of Charleroi and its surrounding region of Hainaut. A self-professed autodidact, he nevertheless received training at the Université de Travail in Charleroi from 1914 until 1919, starting his professional life working for an interior decorator, painting faux marble and wood grain.[1] Delmotte himself repeatedly emphasized in interviews and essays this artisanal aspect of his origins and his insistence on an independent path. In an autobiographical essay, he recounts that he learned what he needed to know through his independent study of nature, plaster casts, and the golden section, studying each for a set period of years from 1915 to 1939.[2] Major old masters also played a significant role in his development; Piero della Francesca, Caravaggio, Poussin, and David stand out as the most important of his early influences. He remained aware of current artistic developments in Europe during the early twentieth century, although he dismissed his engagement with them as merely casual, “visiting museums and exhibitions as one scans the columns of the local newspaper.”[3] Nevertheless, Giorgio de Chirico’s metaphysical dreamscapes, undoubtedly known to Delmotte through the exhibition Minotaure in Brussels in 1934, are a clear source of inspiration in their exploration of dream states, alternate realities, and classicizing forms, as are the contemporary Surrealist works of René Magritte, Max Ernst, and Salvador Dalì.[4]

A formidable list of gallery exhibitions of Delmotte’s work during his life, either independently or as part of a group, indicate that he was a known and successful figure in art worlds of Belgium and Europe. His two most significant exhibitions were “L’Humanite en Marche” with Galerie Isy Brachot in 1969, and a retrospective of his work with Isy-Brachot in 1976. The majority of public exhibitions of his work were with Galerie Isy Brachot in Brussels, or through subsidiary outlets they sponsored, but his work appeared in galleries as far afield as Turin, New York, and Tokyo. His fame continued briefly after his death, culminating in an international exhibition organized by Galerie Isy Brachot and Nahan Galleries in 1991.

Perhaps because he seems to have preferred to keep out of the limelight—staying largely regional in his aspirations and remaining seemingly apolitical during a time when other artists were actively voicing their struggles against the political and aesthetic authorities of the early 20th century—Delmotte seems to have evaded broader scrutiny. Verifiable facts about Delmotte’s career are scarce, in part due to his reluctance to acknowledge them in his own accounts of his life, but also because few historians or critics have engaged with his work to date. Thus far, the two major assessments of his career—a 1969 monograph by Waldemar George and an essay by Robert C. Morgan for a 1991 catalogue to accompany the exhibition of Delmotte’s work organized by Nahan Galleries and Galerie Isy Brachot—read more as philosophical musings on his work rather than scholarly investigations into his life and motivations.[5] In Delmotte’s work, George found an enduring humanism, albeit tinged with apocalyptic visions and the embrace of decay, while Morgan suggested a more cynical interpretation informed by Nietzschean philosophy. Delmotte himself steered away from any particular interpretations of his work, in fact acknowledging that a viewer’s interpretation of a work may be entirely different from the one he intended when it was created. For him, the interpretation of the work--truly understanding it--came from the work itself, the context in which it was created, and the methods used to construct it. He consistently distanced himself from being categorized, typically as a surrealist, stating “The ‘ism’ is a cheap way to give yourself a personality.”[6]

Nevertheless, viewers familiar with the history of art can identify the sources that must have inspired this Belgian modernist’s works. His marmoreal figures recall the hard-edged structuralism of Piero della Francesca, Poussin, and David, while his jewel-like tones and microcosmic details conjure up memories of early Netherlandish paintings on panel, and his serpentine yet angular nudes reveal a deep appreciation for Italian Renaissance and Mannerist models. In his often macabre subjects and the erotic presentation of his figures, he shows himself to be closely allied with the Symbolist traditions of Belgium, recalling the work of Ferdinand Khopff and Felicien Rops. Delmotte does not attempt to hide his reliance upon these traditional resources, rather he arguably uses their recognition factor as a means to make his art address broader, enduring concepts that speak to the human condition. His time-honored subjects from mythology, the Bible, literature, or nature are rendered so idiosyncratically that their resulting interpretations are far from commonplace. Attempts to dismiss Delmotte’s work as derivative or hackneyed are countered by its stubborn individuality, resisting any overt classification with those of his Surrealist or modernist contemporaries. To look at a Delmotte painting is to engage with the idiosyncrasies of the artist’s worldview. At a time when these avant-gardes were subverting the established traditional subjects of the “ancients” in favor of disruptive explorations of the readymade or conceptually-based minimalist works, Delmotte celebrated the manual aspect of painting, using it to reinvent the traditional subjects and themes it depicted for centuries. For Delmotte, the manual act of painting never stopped being a relevant and essential means of exploring the human experience.

Delmotte’s technical mastery is evident, exploiting color values, sculptural form, and gesturally wrought facture in such a way--often on a monumental scale--that contributes to the meaning of the subject depicted. Delmotte stated that the large scale of his works allowed him a latitude of expression that was otherwise curtailed by more restrained proportions.[7] As in the works of his illustrious old master predecessors, Delmotte’s paintings of even disturbing subjects nevertheless woo the viewer through their mesmerizingly detailed and subtle technique. Even his colorful still lifes that seem to celebrate beauty for its own sake contain, upon closer examination, ruptures in surface that evoke the inevitability of their own decay. Similarly, his landscapes are constructed by a generative force evident in the artist’s bravura handling of the paint; the worlds he created came into being through the artist’s manual effort to create them. Both his traditionally weightier, painted subject matter and the frivolity of his pen sketches of imaginary creatures convey an intensity of production--both through highly wrought material means and prolific output. For Delmotte, the impetus to create was constant. It is his highly personal treatment of these subjects that keeps us looking at his canvases which remain as elusive and fundamentally inscrutable as their author.

Andaleeb Badiee Banta

[1] “Autobiography and Thoughts on Art by Marcel Delmotte,” in Waldemar George, Le monde imaginaire del Marcel Delmotte. Paris, 1969, 225.

[2] “Autobiography and Thoughts,” 228.

[3] Galerie Isy Brachot, Exposition Delmotte: peintures de 1916 à 1950. Brussels, 1976.

[4] Jean Clair, Marcel Delmotte (1901-1984), oeuvres de 1919 à 1950. Paris, 1987.

[5] George 1969 and Nahan Galleries, Marcel Delmotte, with essay by Robert C. Morgan. New York, 1991.

[6] “Autobiography and Thoughts,” 230.

[7] “L’Humanite en Marche,” Radio interview with Magda Palatchi, 16 January 1969; transcription cited in George 1969, 233-34.