JAN BOGAERTS

(‘s-Hertogen Bosch 1878 - 1962 Wassenaar)

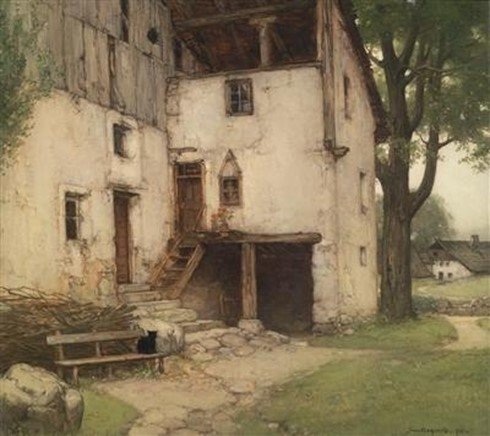

House with a garden in Vogezen

Signed lower right JanBogaerts 1912

Oil on canvas

16 x 20 inches (39 x 49cm)

Provenance:

Private collection, The Netherlands

Jan Bogaerts was born in the Dutch city of ‘s-Hertogenbosch, in the province of North Brabant, in 1878. As a child he had dreamt of becoming a violinist, yet – perhaps guided by the example of his grandfather Cornelis Bogaerts (1812-1888) who had been a painter – in 1893 he enrolled at the local Royal School for the Applied and Visual Arts, which would later come to be known as the Royal Academy of Art and Design. His teachers included Piet Slager (1871-1938), Antonius Godefridus Schull (1819-1896) and Antoon van Welie (1866-1956), all noted portrait painters of the age. During his studies at the Royal School, Bogarts received several awards and honourable mentions, and also began to work as an assistant in the studio of van Welie.

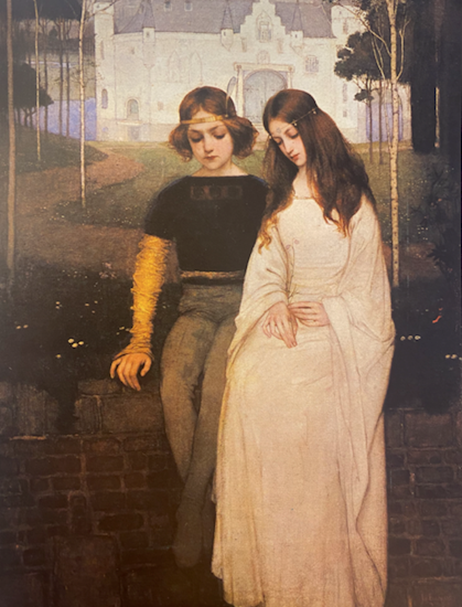

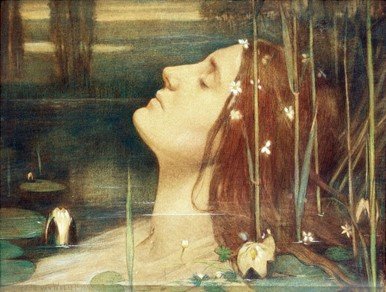

In 1899, Bogaerts left ‘s-Hertogenbosch to continue his education at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Antwerp, where he was taught by brothers Juliaan (1842-1935) and Albrecht (1843-1900) Devriendt, both exponents of Belgian history painting. The influence of their romanticised medieval narratives, alongside that of van Welie’s Symbolist works from the 1890s, is visible in Bogaerts’ Two Children of the King (fig. 1) from 1900-01, thanks to which he was awarded a pension to stay on at the Academy. The composition shows a boy and a girl, dressed in clothes of medieval inspiration, sitting pensively against the backdrop of a fairylike castle, complete with moat and winding path flanked by slender birch trees. Its wistful atmosphere echoes that of van Welie’s Ophelia and The Princesses of Legend (figs. 2-3), two works from 1899, which seem to have also inspired the melancholy features of Bogaerts’ royal children.

In 1903 Bogaerts returned to ‘s-Hertogenbosch, where he began his career as an independent painter. His work gradually moved away from the historical themes of the Devriendts and the contrived lyricism of van Welie, focusing instead on still lives and landscapes, alongside a number of portrait commissions. The still lives, with their care for detail and close attention to the effects of light and reflection on different surfaces, are reminiscent of their predecessors from the Dutch Golden Age, yet less compositionally exuberant. A similar restraint characterises Bogaerts’ landscapes, in which nature and buildings exist unhindered by the passage of man or the disruptive force of machinery.

The present canvas, signed and dated 1912, perfectly exemplifies Bogaerts distinctive approach to landscape. Set in the Vosges - a range of mountains in Eastern France, south of Strasbourg - the view opens onto a tranquil garden and a house, its white walls and slate roof set against the trees and meadows of the valley beyond. The grass, flowers and leaves are painted - in a style that looks to the Barbizon School - with light, speckled brushstrokes, which grow broader as the trees fade into the distance. The more saturated pinks and yellows of the petals create highlights amongst the predominant white, green and blue hues of the palette. Hollyhocks are recognisable on the left hand-side of the canvas, framing one of the windows of the house, where the white curtains are partly drawn yet reveal nothing of the interior. Man’s presence, referred to yet not visualised, is a regular undercurrent in Bogarts’ landscapes, and perhaps endows them with a timeless quality that, compared to the historicism of his teachers, is what constitutes the essence of his individuality as a painter.

In 1913 and 1914 Bogaerts continued to focus on landscape, exploring the theme in a series of paintings inspired, like our view of the Vosges, by his travels. In 1913 he was in Luxembourg, where he painted a panorama of Echternach, its bridge reflected in the calm waters of the river Sauer and the town shaded by tress and embraced by the hills behind it (fig. 4). The treatment of the houses and of the white stone of the bridge, executed with carefully applied layers of whites, creams and greys to convey the texture and age of the materials, is similar to that Bogaerts employed for the house in the Vosges, and is repeated in compositions such as Monastery near Echternach (1913, fig. 5), The Petit Trianon at Versailles (1914, fig. 6), and The Moat at Castle Genhoes, an old manor house near Valkenburg (1915, fig. 7).

At the outbreak of World War I, Bogaerts was living in Teteringen – a village in North Brabant – with his wife Sofie. His paintings had by then received public recognition, their serene and intimate quality arguably offering contemporaries a form of refuge from the war, even reassurance that not everything could be engulfed by the horrors of the conflict. In 1915, the renowned art dealers Boussod, Valadon & Co. organised an exhibition dedicated entirely to Bogaerts’ work in The Hague (Tentoonstelling van schilderijen en teekeningen door Jan Bogaerts). The firm – which had been until 1884 known as Goupil & Cie and is the same that in the 1870s and 1880s counted amongst its Paris senior staff the brother of painter Vincent van Gogh – constituted a major force in the European art market, and its stock books are now preserved in the Getty Research Institute. Several entries from the 1910s are for paintings by Bogaerts, which suggests a close relationship between the artist and Boussod, Valadon & Co. One entry dated 31 December 1912 records a painting titled The Old Manor House (Le Vieux Manoir), which can be identified with one published by critic Maria Viola in 1916 for the Dutch magazine Elseviers (fig. 8), and shows a composition that bears close resemblances to the present canvas.

In 1922, after a four-year stay in Voorburg, Bogaerts settled in Wassenaar, north of The Hague, where he lived until his death in 1962. His output shifted more pronouncedly towards still lives, yet a painting of a garden in Wassenaar from 1922 (fig. 9) shows him continuing to explore outdoor subjects, as do a group of canvases executed during a sojourn in South Tyrol, Italy (figs. 10-11), where he was fascinated by the traditional Alpine houses of local families, their white-washed walls perhaps reminding him of those he had admired many years previously in Northern Europe.

Throughout the 1930s, Bogaerts’s reputation continued to grow, and his paintings were the subject of exhibitions in Tilburg (1932), Nijmengen (1933), The Hague (1935) and his native ‘s-Hertogenbosch (1938). In 1942, he was appointed an honorary member of the Provincial Society for the Arts and Sciences and six years later, on his seventieth birthday, another exhibition dedicated to his work was inaugurated in ‘s-Hertogenbosch. In 1950 he was invited to exhibit in a group exhibition curated by the influential Pulchri Studio in The Hague. He continued to work until the late 1950s, and died in Wassenaar in 1962. In 1978, the Noordbrabants Museum in ‘s-Hertogenbosch celebrated Bogaerts’ legacy in an exhibition that, with the help of his heirs, gathered paintings and drawings from several private collections, and constitutes the most complete catalogue of his work to date (Jan Bogaerts, 1878-1962: schilderijen en tekeningen). Today, Bogaerts’ work is enjoying a gradual rediscovery. The Rijksmuseum Twenthe in Enschede owns a Still Life of Roses from 1920, and the Toledo Museum of Art recently purchased a Still Life with Azaleas, painted the same year as the present picture.